|

A Paper Trail

|

Scattered on a studio floor, tacked above a desk, bound in small books or stored in archival drawers, an artist's work on paper has always been of particular interest to me. Follow my gallery wanderings and studio visits to discover unique works on paper.

|

|

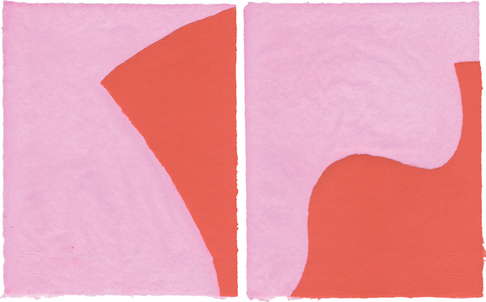

This was my favorite greeting card this season. After coming across Win Knowlton’s name only occasionally in the past decade, the image prompted me to call the artist directly knowing he wasn’t represented by Dinter Fine Art, the gallery that sent the charming, gouache evergreen. Knowlton kindly offered to show me his work, my having expressed a yen for – surprise, surprise – his “drawings” on paper. I recognized the heady abstractions the moment he pulled them carefully from their archival storage drawers and was thrilled to see them in succession – varying sizes, changing palettes, dense and transparent forms, all on unique papers. There is an affinity here for the natural world, and I was interested to hear that Knowlton also works as a professional horticulturalist in public and private gardens. Reluctant to affirm that one informs the other, he is happy to engage in both disciplines with meaningful commitment to each craft. I had just come from the Inventing Abstraction show at MoMA and saw a bit of Marsden Hartley in his rounded, geometric forms. Hartley had a healthy respect for forms and often outlined his representational images in black for emphasis, flattening their planes. Knowlton does not use outlines as his abstract forms suffice, the white ground that surrounds them providing sharp relief. Philip Guston, too, comes to mind, an artist Knowlton admires. There is also a bit of Hockney here and there, the translucent blues, the water, the shorthand of repeated brushstrokes. But sometimes I see what I want to see. Having always focused on Knowlton’s drawings, I realized I had neglected the importance of sculpture to his body of work. Fortunate to see it in situ, I was taken with its whimsy. There were containers – filled, small objets on tabletops and perforated, wiry forms, suspended, with birds and orbs. Again, there is a connection here – in the forms he plays with, artfully, the materials he mines, and the affinity to a natural world he closely observes, consciously or not.

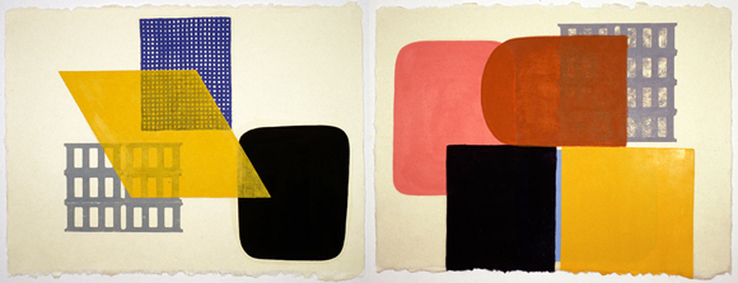

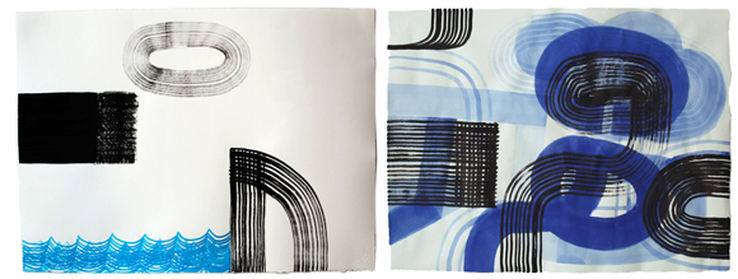

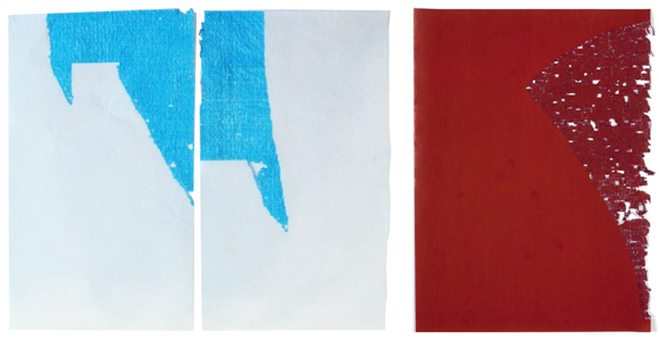

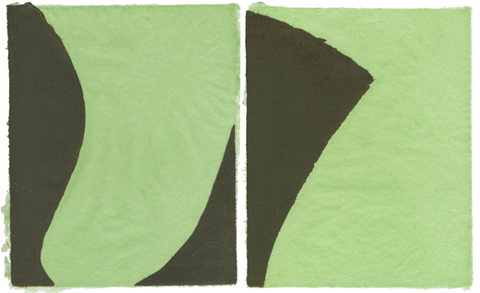

I have just come from the workshops of Dieu Donné Papermill in New York City. As an enthusiast and blogger of fine works on paper, I have always had Dieu Donné on my regular New York City beat. Interactive and collaborative, Dieu Donné works with both prominent and emerging artists, as well as students, to produce beautiful editions and unique works on hand-made paper. Rarely do I visit the studios without coveting their latest production. Often experimental, the work seems to expand the language of the working artist to explore a vocabulary that he or she discovers in the process. Given the fine quality of the various hand-made papers available, it is often this medium that gives rise to the innovation and finesse of the finished edition or individual work. My most recent visit focused on the work of Allyson Strafella. Her original abstractions on paper have been widely exhibited and show a rather obsessive, mark making impulse. Using a typewriter much like the Smith Corona of my father’s I used in high school, Strafella uses a single key, most often that of the colon, to tap, tap, tap her way to a composition that wears thin with her efforts. Carbon paper is both her medium and her drawing plane, revealing two compositions when complete – that of the paper beneath and the worn carbon sheet itself. Positive and negative. Both compelling and worthy of exhibition. Strafella's typewritten compositions Strafella’s most recent work with Dieu Donné uses shapes that are familiar to those tapped out in her carbon works, but instead of subtracting the paper mass with her efforts, the pigmented cotton she adheres to the abaca “paper” sheet gives the surface of this work an almost tangible dimension or form. With white-gloved hands, I found myself rearranging the 10 ½ by 8 ½ inch sheets as if I were solving a puzzle or trying to piece together a complementary arrangement. Nothing fit exactly but all of her shapes seem to posit an equilibrium that works. A single page exhibited on its own works as well, the ethereal base sheet almost miraculously holding on to the heft of the “printed” form created in this papermaking process. Strafella's variable edition work from Dieu Donne entitled "Spell" Another stunning pair from Strafella's "Spell" edition

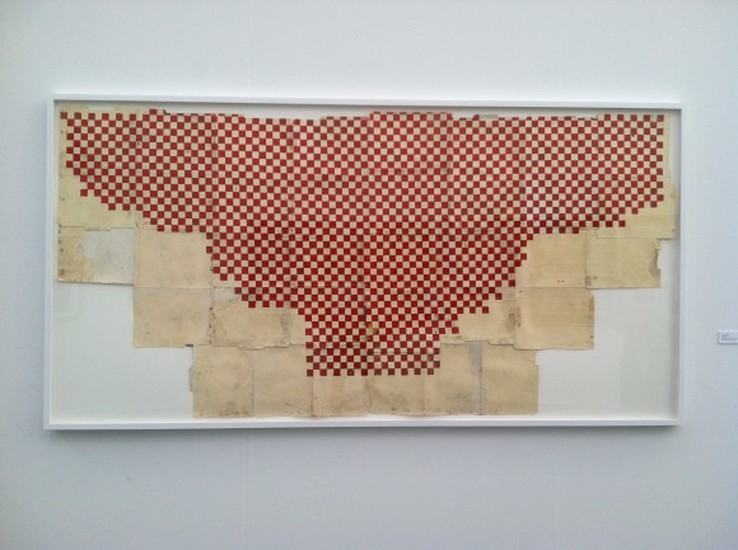

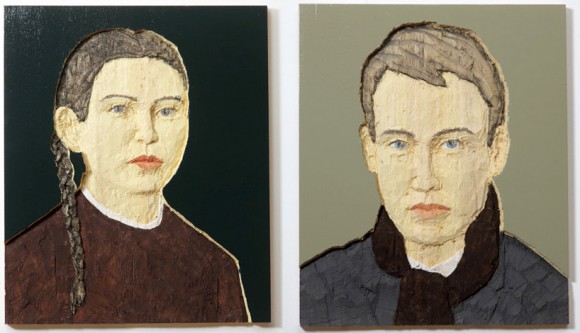

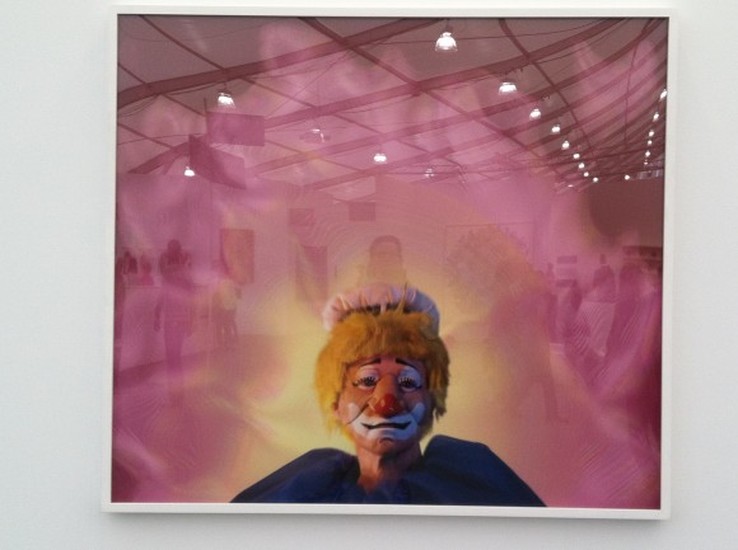

Despite popular thought, the circus and the fairground are of British, not American, origin, and so it seemed appropriate that last week’s Frieze Art Fair, founded in London in 2003, came to town in carnival-like guise for its New York City debut. With a bespoke tent designed by SO-IL architects of New York, colorful, gourmet food trucks, and the well heeled of NY in typical art world costume, Frieze had all the trappings of an amusement park. Even getting to the Fair was its own sideshow. Departing from 35th Street on the East River of Manhattan, I boarded a checkered water taxi and was ferried up river to Randall’s Island, site of Frieze 2012. Oh, what a ride. Adhering to my quest for outstanding works on paper, I navigated the chock-a-block booths of the big top and found some winners. William Cordova uses detritus and its often strange histories to compose both installations and works on paper that refer to transitions he endured as a Peruvian in various adopted homelands. His multi-lingual references point to experiences lived, some comforting, others thorny with icons of his personal struggle. Polish born Piotr Uklanski exhibited his work at Massimo de Carlo, a Milan gallery. An artist that works in a variety of mediums, including video and sculpture, Uklanksi’s recent compositions of layered paper mounted on wood were almost pop in their sensational pull to come closer. The ocular reference in the center of each work was a surprising and somewhat disturbing discovery. Because most paper originates with wood, I will include the stunning, carved portraits of Stephan Balkenhol. At once familiar and displaced, Balkenhol’s sculpted reliefs represent a sort of post-modern everyman, faces we can engender with our own associations. Carved with a chisel and hammer and painted with matte, uniform colors, the narrative of these portraits is ours to own. One of Peter Doig’s ravens from the Corbeaux series of monotypes caught my eye. Inspired by a work of Georges Braques, Bird, Doig’s raven is determined in flight, buoyed by the pastel clouds that silhouette his primitive form. Leaving the Fair at the end of the day, a photo of Cindy Sherman’s bid farewell. The artist’s burlesque visage was in contrast to the countenance of spirited dealers and carnies that had come town for the Frieze Fair. Perhaps the expression was simply a knowing nod to the coming weekend of exhibit and entertainment for an audience of art enthusiasts. As performers know – the show must go on.

The artist Anne Truitt distills a remarkable range of experience into form and color in this quiet arrangement of drawings at the Matthew Marks Gallery. How do I know? I have read Daybook, a journal of Truitt’s, and consider its fierce kernels of truth to offer a guide, a point of departure for the viewer who, like myself, might struggle to delve beyond the simple elegance of the exhibited illustrations. As a devoted fan of Truitt’s writing, I revisited the account of her life in these abstract compositions while allowing myself an experience of my own as I imagine she would have encouraged me to. I was swept away, circling the gallery space not so much looking for clues as assigning her colors, lines and shapes sensations of my own. Truitt is most well known for her formal abstract sculptures, disciplined columns of construction and color that grace many American museums and private collections. Her works on paper are a complement to the sculptural work, compositions in their own right and distinct from the drawings she made, often in preparation for the three dimensional forms. I am usually drawn to work on paper that is more organic, natural and exuberant. Truitt’s work is so calibrated, precise and controlled, bearing little relation to the flux and incongruities of the natural world around us. And yet, having read her prose, I see her shapes and colors as infused with the enduring content of her life – the complexity of pain, pleasure, triumph and failure that composes our collective everyday lives.

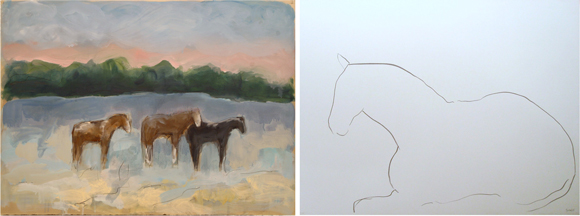

Spend some time looking. As Truitt once said in the aftermath of what was often harsh criticism of her work, “There is a small center into which conception can arrive. And when it arrives, you make it welcome with your experience.” Advice to heed at your next museum tour or gallery show. A holiday visit to the Teton Mountains in Jackson, Wyoming brings only one thing to the mind of an enthusiastic skier. Powder. How do I get some, guaranteed, and then, how do I get some more? It is not easy. This year, we arrived in Jackson to scratchy slopes and rocky bowls. But we started the valley snow dance, and the clouds moved in, dumping several feet of perfect pow pow for our week’s stay. Most après ski in Jackson is made up of a hot tub and a cold Snake River brew. I broke with the ranks one evening, however, to check out the local art scene. The village of Jackson is home to several established galleries showcasing a wide variety of decidedly “western” art. Teepees, cowboys and mountain vistas abound. Native American art is popular and wildlife studies have a heritage in the proximity of the National parks, home to bison, moose, bear, bobcats and more. Having seen the snowy backs of bison on our way into town, I focused on sketches of life in the valley during the winter months, skiers excepted. Mary Roberson, presently exhibited at Altamira Fine Art in town, illustrates Yellowstone’s wildlife while camping in the Park. Her affinity for these animals at rest or on the prowl for sustenance is remarkable. Theodore Waddell sees himself as an artist in the modernist tradition. A native of Montana and a rancher for many years, Waddell has spent hours observing his horses and cattle along the riverbed and against the Bridger Mountains. I saw the work of Georgia-based artist Helen Durant on my final day in Jackson. Hearing the Four Seasons Hotel had a notable collection of fine art; I toured the halls in my boots. Durant’s formidable bears, in a poorly lit hallway en route to a conference room, took my breath away. I assumed they were painted on paper due to an uneven surface on fine, unstretched canvas and its protective glass covering. I had to include the bears in my Jackson menagerie. The fellow wolf, drawn on paper by Durant, shows her virtuosity on this medium as well.

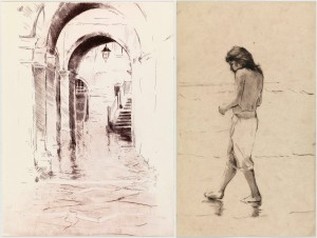

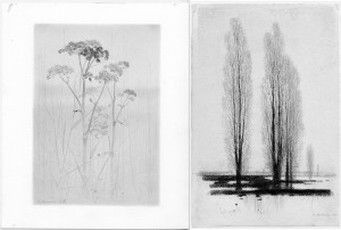

This year, Art Basel Miami Beach and its satellite art fairs brought sunshine and glamour to the visiting masses, all the while offering substantial grist to the quietly growing art mill of America’s renowned gateway city. Kardashian look- alike contests and references to the “Super Bowl of Art” aside, to those of us in sensible shoes with canvas tote bags, the panoply of shows, private collection openings and riot of public art offered several days of foraging for art treasure. Heat and humidity can be unkind to paper, so I was curious as to what dealers had brought along knowing that climate-controlled venues would be taxed at best. And, indeed, the lights went down and the temperatures up at one of the largest of fairs, but the paper held its own. As a result, the need for closer scrutiny revealed some gems. Joan Linder’s botanical drawings were spectacular. Known for a variety of ambitious drawing projects, including anatomical lab studies and plein air gallery installations, Linder’s quill and ink are a powerful medium for her detailed observations. Seonna Hong’s paintings on paint chips caught my eye. Her background in animation lends a storytelling aspect to these brightly colored rectangles. Part of her Tectonic Plate series, this work indeed seems to shift and come to life the closer one looks. Jeanine Cohen made the trip to Miami from Brussels for the Scope Miami fair. I had the pleasure of meeting the artist to discuss the minimalist works on paper exhibited alongside her larger, painted wood constructions. Carefully incised lines pierce the surface of these works with precision. Unfolding just so much, to me, they recall the jalousies of old Florida. As inspiration, Cohen has photographed the dramatic angles of buildings in Tel Aviv as well as the familiar windows that frame views to her backyard garden. She is a world traveler and this work easily invites imagination and wanderlust. Paul-P. The early November IFPDA Print Fair in New York is always a favorite for a works on paper hound like me. Printed matter, old and new, is presented chock-a-block in the Park Avenue Armory at 67th Street and runs the gamut from woodblocks to cutouts in a timeline that spans five centuries. The big guns – Warhol, Close, Katz, Cottingham and others – claim prime wall space with hefty price tags reflecting an increasing dominance of contemporary sales in the print market. The familiar Diebenkorn “Ocean Park” pieces, a suite of Louise Bourgeois’ etchings at Galerie Boisserée and a boyish Mapplethorpe multiple by Elizabeth Peyton made up my imaginary wish list predictably quickly.But this time around, it was the unassuming work of Paul P. and Gunnar Norrman that held my interest, slowly revising my choices in a field of favorites. In a familiar sea of cleverness and cutting edge printing technique, the small works of Norrman and Paul call attention to their craft – a draftsman’s mastery of line and the exquisite play of light and shadow on their subject matter. Canadian-born Paul P. is best known for his evocative portraits of young, gay men as well as his more recent atmospheric landscapes. The small editions of his etchings at Poligrafa recall Whistler – brooding observations of foreign cities and portraits of friends, tenderly observed. Gunnar Norrman

The late Gunnar Norrman, a Swede who was an avid gardener and accomplished pianist in addition to being a skilled draftsman, used conté crayon, pencil and drypoint to create a breathtaking body of work in his lifetime. Whether observations made at a cool distance or details scrutinized with the eye of a botanist, Norrman’s drawings of the natural world are some of the best I have seen. As Ken Johnson put it in his New York Times review of this wonderfully rich but clearly contemporary-heavy fair – here “the old is more refreshing than the new”. With an obvious debt to “old” masters exhibited – Munch, Cassatt, Whistler and others – the work of Norrman and Paul P. holds its own, making old school look surprisingly new. I first came across Thomas Müller’s drawings in Miami two years ago. With my head awash in the visual onslaught of Art Basel Miami Beach, the (seemingly) informal arrangement of his simply framed drawings in Patrick Heide’s London booth brought welcome relief to a show-weary art consultant. A closer look, and I was hooked. Three hours later, and I was dragging my companions back for just one more look.

Born in Frankfurt in 1959, Müller lives and draws in Stuttgart Germany, while exhibiting his work all over the world. A prolific artist, Müller seems to thrive in the field of experimentation, creating new structures and compositions as a musician would. Like lyrical scores, these compositions are not illustrations but arrangements that use a personal vocabulary of symbols and marks. Müller works with a variety of traditional mediums to make these notations. Oil crayon, acrylic, graphite pencil, watercolor, ballpoint pen and chalk, two or three often used together, find familiar ground on his handmade paper. Müller’s urge to make marks is a personal gesture I find beckons the viewer to his work. Often I find myself scrolling through a file of his work after a long day on the New York gallery beat. In much the same way, I will look forward to the welcome pause his work offers in the visual heat of Miami art fairs come December. Encountered in a small annex of the Robert Miller Gallery in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City, they took me by surprise. Small in stature compared to the grownups mounted on aluminum by the same artist in the large adjoining galleries, the modestly framed portraits captivated me with a familiar charm. Painted on paper by the artist Robert Greene, the fifteen or so exhibited works are colorful, abstract portraits of the painter’s friends, family and canine companions. The texture of the oil paint is gestural, impastoed in a way that suggests the artist is calling out the names of his childhood friends or immediate neighbors. Hailing “Uncle Herbert”, “Connor”, his stepson, and “Sari”, his brother’s wife.

Robert Greene has always admired industrial design, color and the monumental scale of the natural landscape. This most recent work harkens back to his narrative landscapes of the 1980’s where he captured familiar figures in romantic settings. Representational, with Corot-like skies and decorative elements that recall Marsden Hartley and Alice Neel, those early paintings revealed places of emotional escape. In a similar way, the new works, both large and small, do the same, but in a more visceral way, zooming in on the color and texture he loves to reveal a more honest and mature emotional landscape. But it is in the intimate scale of his works on paper that Greene’s methodical constructions of narrow vellum strips strike a chord. The elegant patterns and sweep of the larger work that has graced fine homes and Chanel boutiques give way to a painterly reminiscence that is entirely without guile. |